Yapulpa (Glen Helen Gorge waterhole), west of Alice Springs

Fig. 1: Peggy Griffiths, Butterfly-Ngarrangkarni - Keep River Country, ochre pigments on canvas, 80,5 x 100,5 cm, printed in: Altendorf, Ulrike and Hermes, Liesel (ed.): Australien - Facetten eines Kontinents, Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2010, p. 125

Fig. 2: Rover Thomas (Joolama) (ca. 1926-1998), The Burning Site, 1990, ochre pigments on canvas, 90 x 180 cm; printed in: Thomas, Rover, Akerman, Kim, Macha, Mary, Christensen, W. and Caruana, Wally: Roads Cross. The Paintings of Rover Thomas, Craftsman Press, Victoria 1994, p. 56

The Meaning of Country

The First Australians have a special relationship to land. Land (or “country”) is not only a material entity, which provides food and medicine, but also a spiritual one. It cannot be possessed, only administered. Country is equivalent to a “spiritual home”. (1) Land and landscape are not apperceived simply as visible entities, but are known quintessentially. Each person belongs to a certain part of the country, just as obversely that part of country belongs to him.

The First Australians have a special relationship to land. Land (or “country”) is not only a material entity, which provides food and medicine, but also a spiritual one. It cannot be possessed, only administered. Country is equivalent to a “spiritual home”. (1) Land and landscape are not apperceived simply as visible entities, but are known quintessentially. Each person belongs to a certain part of the country, just as obversely that part of country belongs to him.

The essence or identity of a person is thought to exist in their country even before they are born. It is therefore not surprizing that the government policy of forced resettlement of indiginous peoples, from their own country into distant regions, which began around the turn of the 20th century and persisted into the 1960s, is counted as one of the most damaging policies. Conversely, the increasing recognition of political freedems in the early 1970's immediately resulted in an outstation movement (“returning home” movement) as people returned to their country, from which they had been exhiled.

“People talk about country in the same way that they would talk about a person: they speak to country, sing to country, visit country, worry about country, feel sorry for country, and long for country. People say that country knows, hears, smells, takes notice, takes care, is sorry or happy … country is a living entity with a yesterday, today and tomorrow, with a consciousness, and a will toward life.” (2)

Therefore, also in the Indigenous Australian creation stories, country is fundamental; whereas in the Christian religion the Word is primordial, in the religions of the Indigenous Australians it is country.

Relationship between Painting and Country

The connection between paintings and country becomes clear using a painting by Peggy Griffiths:

The connection between paintings and country becomes clear using a painting by Peggy Griffiths:

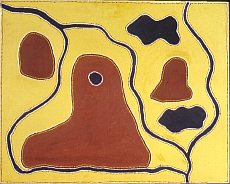

The painting entitled “Butterfly Ngarrangkarni - Keep River Country” (Fig. 1) shows the country of the artist’s grandfather in the area of the Keep River National Park in the Northern Territory, just across the NT/WT border from Kununurra, where the artist lives and works. Concerning this painting, she said:

“This country is associated with the Butterfly Tjukurrpa. The big brown hill at the center of the painting is Libeninanyambingiya where the butterfly camped in the dreamtime. The black circle is the cave where he had his camp. The other brown areas are hills in the surrounding contryside and the black areas are springs. The black lines are branches of the Keep River which flows through this country.”

The artist recounted at first only one theme of the painting, but she went on to explain that her grandfather was killed in this country by white settlers who were looking for forced Aboriginal labour to build their cattle station.

Replying to a question about the meaning of the butterflies, which the artist describes as “camping” in the cave – although butterflies cannot camp, only humans do that – she answered that: first of all, there is actually a cave in this area, in which many butterflies live; secondly, the country is portrayed in the painting in association with the butterflies as creator ancestors of specifically this area of country; and thirdly, the actions of the butterflies have an important part in the dances which are held there.

Thus, the painting portrays the relationship between the country, which belonged to the grandfather of the artist, with (a part of) the Creation, which is celebrated again and again in appropriate dances, and with the history of persecution of black Australians by the whites, since the work was painted in memory of the death of the grandfather.

Connection between History and Country

Rover Thomas (Joolama) shows another connection between recent historical events and country in his painting “The Burning Site” (Fig. 2). The artist spent most of his life working on various station properties, about which the local oral histories relate that, during the so-called “Killing Times” at the beginning of the 20th century, massacres were committed on the Indigenous Australians. The artist made this a theme of his painting.

The large coloured area on the right represents a mountain, Mount King, and also symbolizes the souls of the Indigenous Australians who were poisoned with strychnine on the Bedford station property. The black, nearly circular shape near the top stands for the place where the dead were burned. The indentation below it shows the place where firewood was collected and at the lower edge is the location of the homestead of the Bedford farm, discernible for those versed in this history. The narrow brown lines represent various paths or tracks. It is the country seen from above, in which the event of the massacre is localized/embedded. By means of a pictorial portrayal of the event (massacre) as part of the relevant country, the artwork incorporates the cultural remembrance of the recent history, anchored in the fundamental immemorial relationship between oral histories and the country.

The large coloured area on the right represents a mountain, Mount King, and also symbolizes the souls of the Indigenous Australians who were poisoned with strychnine on the Bedford station property. The black, nearly circular shape near the top stands for the place where the dead were burned. The indentation below it shows the place where firewood was collected and at the lower edge is the location of the homestead of the Bedford farm, discernible for those versed in this history. The narrow brown lines represent various paths or tracks. It is the country seen from above, in which the event of the massacre is localized/embedded. By means of a pictorial portrayal of the event (massacre) as part of the relevant country, the artwork incorporates the cultural remembrance of the recent history, anchored in the fundamental immemorial relationship between oral histories and the country.

Notes

(1) Lüthi, B. (ed.): Aratjara. Kunst der ersten Australier, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, DuMont, Köln 1993, exh. cat., p. 358, ISBN 3926154160

(2) Rose, Deborah Bird: Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness, Canberra 1996, p. 7, ISBN 0642235619

(3) Ngarrangkarni is the designation in the language of the Gija of the meaning behind all things (i.e. metaphysics), see Jukurrpa