Fig. 1: Rockpainting in northern Australia

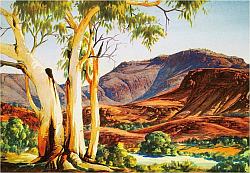

Fig. 2: Albert Namatjira, In the Ranges, Mount Hermannsburg, ca. 1950, watercolours and coloured pencil on paper, printed in: Benjamin, Roger and Weislogel, Andrew C. (eds.): Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, New York 2009, p. 29

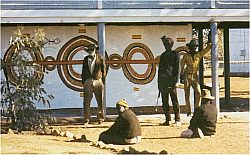

Fig. 3: Papunya Schulmauer, Juni-August 1971, printed in: Bardon,

Geoffrey und Bardon, James: Papunya. A Place Made After the

Story. The Beginnings of the Western Desert Painting Movement,

Melbourne 2004, p. 17

Introduction to Indigenous Australian art

The painting on natural bark sheets using ochre pigments and natural fixatives was, after rock painting, the next advance in the art of the First Australians. It is unknown when it was developed or how widespread it became. Various Australian sources give different and contradictory statements. Certainly it became widespread in the 19th Century, when missionaries and ethnologists carried examples of such works back to European ethnological museums.

The painting on natural bark sheets using ochre pigments and natural fixatives was, after rock painting, the next advance in the art of the First Australians. It is unknown when it was developed or how widespread it became. Various Australian sources give different and contradictory statements. Certainly it became widespread in the 19th Century, when missionaries and ethnologists carried examples of such works back to European ethnological museums.

Painting on natural bark sheets using ochre pigments and natural fixatives was, after rock painting, the next advance in the art of the First Australians. It is unknown when it was developed or how widespread it became. Various Australian sources give different and contradictory statements. Certainly it became widespread in the 19th Century, when missionaries and ethnologists carried examples of such works back to European ethnological museums.

Indigenous art experienced some positive attention in Australian academic art circles in the 1920s, from the Australian artist and author Margaret Preston. Her article “The Indigenous Art of Australia” (1), in 1925, suggested using the modes of expression and aesthetics of the Indigenous artists of Australia in the development of a unique, national art aesthetic. Since a national aesthetics could only become generally adopted on the basis of the broadest possible acceptance, however, she considered that Indigenous symbolism should best be converted for this purpose into decorative designs and widely promulgated. Clearly, Margaret Preston was not entirely free of a certain cultural imperialism. (2)

Indigenous artists have used European techniques and materials since 1926, on the mission station Hermannsburg, 130 km west of Alice Springs. Noteworthy here is the first Indigenous artist to become famous across all Australia: Albert Namatjira (1902-1959). With his landscapes in watercolours, he can be considered the founder of the Hermannsburg school of landscape painting. In contrast to western styles of landscape paintings, his watercolours seldom have a central focal point which draws the eye, and usually all areas of his paintings are executed in equal detail.

Indigenous artists have used European techniques and materials since 1926, on the mission station Hermannsburg, 130 km west of Alice Springs. Noteworthy here is the first Indigenous artist to become famous across all Australia: Albert Namatjira (1902-1959). With his landscapes in watercolours, he can be considered the founder of the Hermannsburg school of landscape painting. In contrast to western styles of landscape paintings, his watercolours seldom have a central focal point which draws the eye, and usually all areas of his paintings are executed in equal detail.

Indigenous women were first encouraged to become commercial artists around 1940, on the Ernabella mission station, where they were also provided with European art supplies.

A next and crucial step forward - not only in painting techniques, but in the whole development of the art scene - was made at the start of the 1970s, in the small community of Papunya, about 250 km northwest of Alice Springs. The art teacher Geoffrey Bardon came to town, to teach the local school children.

Without any success, he tried to conjole the children into creating paintings in the Indigenous stylistic idiom. That goal was impossible, however, because the young children had not yet been initiated into the knowledge of the relationships between country, man, oral traditions and history, nor in their representation in forms and painting, nor into the allowed degree of public disclosure. The inculcation of this knowledge does indeed begin in infancy, however the full scope requires until far into adulthood.

The enthusiasm was correspondingly all the greater, amongst a number of men in the community, when Bardon suggested creating paintings on the walls of the local school. The men first created drafts on paper, a preparatory step rarely encountered today, and within the shortest possible time the walls of the school were covered with paintings. A couple of years later, those same walls were whitewashed over, in an act of official vandalism by order of the local, white, school administration.

The enthusiasm was correspondingly all the greater, amongst a number of men in the community, when Bardon suggested creating paintings on the walls of the local school. The men first created drafts on paper, a preparatory step rarely encountered today, and within the shortest possible time the walls of the school were covered with paintings. A couple of years later, those same walls were whitewashed over, in an act of official vandalism by order of the local, white, school administration.

Working together on the wall paintings led to the men requesting further art materials, and Bardon procured for them acrylic paints and canvas. This created for the artists, for the first time, the possibility of producing their paintings on permanent materials suitable for exhibition. And this opened to them something that – in view of their endemic poverty, bad health care, and negligible possibilities of finding paying work – was and is still extremely important, namely the chance to exhibit their artworks and naturally also to sell them.

The most important aspect, however, was that the men had found a way – in addition to their activities to claim their land rights – to document and communicate the unique cultural knowledge which they had managed to preserve across generations of persecution. (3) Thereby is communication in both directions equally important: towards their own children and descendants as well as towards the non-indigenous society.

The events in Papanya were the initial spark for the explosive expansion of a new art movement, which rapidly developed into a multitude of secular art styles.

Notes

(1) Margaret Preston: The Indigenous Art of Australia, in: Art in Australia 3 (11), March 1925

(2) see Mitchell Rolls: Painting the Dreaming White, in: Australian Culture History 24, 2006, pp. 3-28

(3) see Bähr, Elizabeth: Kurze Geschichte von Schwarzen und Weißen, in: Städtisches Kunstmuseum Spendhaus Reutlingen (ed.): Bilderwelten in Utopia. Holzschnitte und Gemälde von Aborigines, Aboriginal Art Verlag, Speyer 2004, pp. 103-109

Further Literature

Altendorf, Ulrike and Hermes, Liesel (eds.): Australien - Facetten eines Kontinents, Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2010