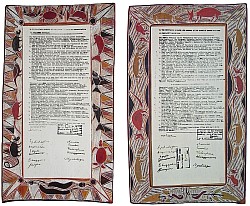

Fig. 1: Yirrkala Artists, The Bark Petition, 1963, ochre on bark, with collage of printed text on paper, 59.1 x 34 cm; printed in: Lüthi, B., ed., 1993. Aratjara. Kunst der ersten Australier. Köln: DuMont, 178

Fig. 2: Kunmanara Queama and Hilda Moodoo, Destruction I, 2002, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 112 x 101.2 cm; printed in: Cumpston, Nici, and Barry Patton, 2010. Desert Country. Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia, 131

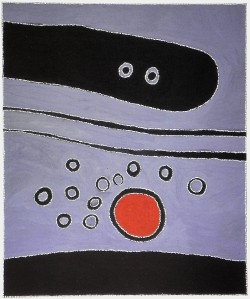

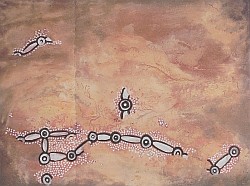

Fig. 3: Jonathan Kumintjara Brown, Old Country – Maralinga Atomic Test, 1995, natural ochres, sand on canvas, 92 x 122 cm; printed in: Sammlung Essl, ed., 2001. Dreamtime. Zeitgenössische Aboriginal Art. Klosterneuburg: Edition Sammlung Essl, 100-101

Fig. 4: Jonathan Kumintjara Brown, Poison Country, 1995, synthetic polymer paint, natural ochres on canvas, 225 x 175 cm; printed in: Cumpston, Nici, and Barry Patton, 2010. Desert Country. Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia, 129

Fig. 5: Lin Onus, Maralinga, 1990, fibreglass, pigment, plexiglass, paper stickers, 163 x 56 x 62 (figure), 125 x 119 x 45 cm (cloud); printed in: Neale, Margo, ed., 2000. Urban Dingo - The Art and Life of Lin Onus 1948-1996. Brisbane: Craftsman House, page 88

Fig. 6: Fiona Foley, Witnessing to Silence, 2004, bronze, water feature, pavement stone, laminated ash and stainless steel; printed in: Foley, Fiona, 2012. “The Elephant in the Room – Public Art in Brisbane”. Artlink, 32 (2) 67 and [19]

Fig. 7: Paddy Bedford, Two women looking at the Bedford Downs Massacre burning place, 2002, ochres and pigment with acrylic binder on canvas, 180 x 150 cm; printed in: Museum of Contemporary Art, ed., 2006. Paddy Bedford. Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art, 89

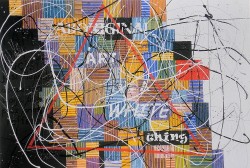

Fig. 8: Richard Bell, Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem), 2003, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 240 x 540 cm; printed in: dOCUMENTA (13), 2012. Das Begleitbuch/The Guidebook, Katalog/Catalog 3/3. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 143

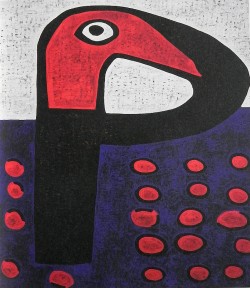

Fig. 9: Gordon Bennett, Home Décor (after Margaret Preston) # 8, 2010, acrylic on canvas, 182,5 x 152 cm; printed in: dOCUMENTA (13), 2012. Das Begleitbuch/The Guidebook, Katalog/Catalog 3/3. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 143

Political Iconography in Indigenous Art

Exerpt from Zeitschrift für Australienstudien 27, 2013, S. 49-66, ISSN 1617-9900, "Political Igonography in Indigenous Art" (20):

It is manifest, from studying the last two decades of Australian Indigenous art monographs, exhibition catalogues, journal articles, and biographies, that a large number of Indigenous urban artists devote much of their art to a protest against racism and neo-colonial policies, or indeed to exposés thereof, or to chronicling of historical events.

The general topic of political iconography has been explored in various national and global contexts (Araeen; Warburg; Warnke), however there seems to be no body of work focusing on the ways in which Australian Indigenous artists use icons to connote, imply or explore political themes.

This article will describe ways and show examples of how artists (both within cities and in remote communities) emphasize political aspects using visual icons. Further examples will be given of artworks which from their content seem to be politically driven, but which are actually intended purely as historical chronicles.

Concerning icons and iconography, this article dares no definitions. For the following analysis of artworks, any visual element which has an associated meaning or connotation is considered to be an icon.

Political Demands and Indigenous Art

“The Bark Petition” of 1963 can be interpreted as one of the first artworks to be recognized as a direct link between modern political demands and contemporary Indigenous art..

Mounted on a bark painting showing the symbols of the respective clans, which authenticates their immemorial relationship to their country, is a typed petition signed by the Elders of Yirrkala. The authors of the petition denounced the annexation of a part of their country for mining, and especially objected to the lack of any consultation process. They appealed to the Parliament and the House of Representatives to establish a commission to consult with the Indigenous inhabitants from Yirrkala before allowing partitioning of their country. Furthermore, they requested that any resulting agreement with mining companies should protect the people of Yirrkala and their independence. No agreement was provided; their land and independence was taken; their country was demolished.

The paintings on the bark are symbols associated with those clans which belong to this part of the country. They are intended as an integral component of the petition, as authentication of the fact that the Indigenous inhabitants have an immemorial right to their country.

“The Bark Petition” corresponds completely, both in its form and its phrasing of requests, to Indigenous traditions of negotiation and compromise, referencing their law, making points politely, and requesting respectful discussions, avoiding confrontation.

The People of Maralinga: Mute Accusation and Mourning

When considering political iconography in Indigenous art, Maralinga in South Australia is an important topic. Between 1955 and 1963, the British set off seven large nuclear explosions and many hundreds of so-called ‘safety’ tests resulting in explosive dispersal of tens of kilograms of plutonium, uranium and other radionuclides (Maralinga 11). Before the atomic explosions, inadequate checks were made on the numbers and locations of the Indigenous inhabitants of these Pitjantjatjara lands (Mattingley 90-91). The result was the death or illness of an unknown number of Indigenous people.

Four artworks concerning Maralinga are presented below. The first is from Kunmanara Queama (1947-2009) and Hilda Moodoo (*1952), both of Pitjantjatjara language group.

The painting “Destruction I” depicts the atomic mushroom cloud in the typical style of dot paintings, with coloured fields of white, yellow and red shading into brown, as well as dotted bands of blue, yellow and brown, separated by white dotted lines which outline the mushroom cloud.

This style of dot painting is quite common in Western Desert Art and differs only in that the painting’s content is represented by a symbol, the mushroom cloud, which is recognizable also in the Western world. The painting gives no hints of outrage or protest against the expulsion of the Pitjantjatjara people from their country, against the destruction of their land or about the two generations’ long fight for restitution, in which Kunmanara Queama was deeply involved.

The painting is a pure representation of a historical event. It is part of a series of works by different artists whose intention was “to pass on their knowledge through their paintings and leave their history behind for others” (cited in Cumpston 130).

The second painting about Maralinga is from Jonathan Kumintjara Brown (1960-1997), likewise a Pitjantjatjara man. Brown was abducted from his mother when only a few weeks old and grew up in a foster family in various cities. As an adult he was able to find his Indigenous mother and other relatives in Oak Valley, Ooldea and Maralinga. His education included Aboriginal Studies and his relatives instructed him about Tjukurrpa, the world view (Weltanschauung) of the Pitjantjatjara people.

His painting contains symbols of concentric circles in black and white, connected by lines and dotted areas, a typical representation of the Pitjantjatjara country. However, the country is devastated, nearly completely obliterated, which the artist portrays by covering the classical symbolism with ochre and sand, obscuring them nearly completely. Nevertheless, the artist says of his work: “There is beauty as well as the other side of it. There is life” (Kleinert 549). Moreover, Jonathan Kumintjara Brown portrays hope appearing through the desolation by structuring the over-painting so that several life-giving river courses are revealed.

A second work entitled “Poison Country” shows again the icons of concentric circles connected by lines. However, here the country is almost expunged by the formless brown ochre. It is a representation of destruction - not only of the country, but also of human life and culture.

Nevertheless, Jonathan Kumintjara Brown said of this painting series: “It is not a protest (…) But I am asking: why did they do this damage to my grandfather's land?” (Cumpston 128).

These are paintings of mute accusation and mourning, unique in Indigenous art in their obliteration of symbols, transforming their absence into a powerful message. The symbols, the Tjukurrpa, are nearly lost, yet still the country - represented by the use of ochre - is present. Anyone confronted by such a portrayal of loss must ask not only why did they do this, but also who ordered it and where is justice?

The final artwork about Maralinga is from Lin Onus (1948-1996). He lived in Melbourne, belonging on the paternal side to the Yorta Yorta people.

The artist began with the well-known (in Australia) historical event of atomic tests at Maralinga and formed it into an attack on the callous indifference to the fate of the Indigenous inhabitants.

The face of the mother, who protects the child in her arms from the invisible atomic cloud, is distorted by a grimace of horror and fear; the hair and clothes of the figures stream in the storm of the nuclear explosion; they stand alone and defenseless. The symbols for radioactivity, which adhere to the cloud, are shown in the colours of the British flag: blue, red and white. They become the colours of death. This emotionally loaded installation is directed against the disdain and contempt shown to the Indigenous Australians; the British and Australian governments were indifferent to the potential death or sickness of Indigenous people remaining in the area. The artwork shows not the event, but the human tragedy. It is thus an artwork of protest and not of historiography.

From these artworks about Maralinga it becomes clear that, within the range of Indigenous artworks about a specific topic, which initially all seem straight-forwardly political, it is necessary to distinguish between various approaches. Some works are purely historical, rendering the event as something to be documented, in order to be able to communicate it to future generations. Other artworks are indeed an accusation against ignorance, colonialism and exploitation, as in Jonathan Kumintjara Brown’s works. Still others are a powerful call to protest, to political action, as is implicit in Lin Onus’ installation.

Political Statements or Historiography

Fiona Foley (*1964) goes a step further with her installation “Witnessing to Silence”. This talented and multifaceted artist imbues her works with references – both overt and enigmatic – to political issues (race relations, indentured labour, dispossession, massacres, land rights, marginalization).

“Witnessing to Silence”, from 2004, is one of 14 works by Queensland artists commissioned for the newly built Brisbane Magistrates Court. Fiona Foley created an installation consisting of bronze lotus lilies, enfolded in mist, accompanied by shining steel columns and by pavement stones set into the courtyard. Each of the pavement stones was engraved with names of Queensland townships. One side of each column is open, showing tall insets of laminated ashes.

Fiona Foley informed the art selection commission for the Brisbane Magistrates Court that her installation refers to bushfires and floods in Queensland (Public Art Agency 17). Some months after the opening of the building, the artist revealed the true meaning of her artwork (Cosic). She had hired a researcher to investigate state archives as well as the available literature on 94 massacres of Indigenous people in Queensland (Allas 58, Foley 64). Fiona Foley engraved the 94 place names on the pavement stones of the installation. Furthermore, the ashes symbolizing fire actually refer to various attempts to conceal massacres by the burning of the bodies. The lotus lilies, which are common in Queensland, represent a second way to eliminate the bodies of murder victims: disposal in rivers or ponds.

The installation is not only an implacable indictment of massacres, it is an accusation which – due to its materials – will adamantly endure and stand like a monument confronting the Magistrates Court. The installation is even more: the artist does not just censure, she reveals a part of Indigenous history which was hidden, buried. And she explores new metaphors to implant knowledge of the persecution into the collective consciousness. She seeks to give Indigenous history an image, a haunting icon.

In that endeavour, Fiona Foley’s installation corresponds with the paintings of the Gija artist Paddy Bedford (c. 1922-2007) and other artists who likewise explored the theme of massacres. Those paintings also reflect on aspects of Indigenous history, but not as images of protest or denunciation. Rather, their representation of the events is to be understood as a historical chronicle, a quasi-impartial description.

Furthermore, such portrayals are often directly and inseparably connected with the location of the incident; the event becomes part of the land and hence part of the Ngarrangkarni – the Gija name for their world view – which is the heritage held in trust for future generations. This particular painting by Paddy Bedford represents the Bedford Downs massacre, whereby as retribution for the killing of a bullock a number of Indigenous men were given poisoned food and their corpses were incinerated.

The installation by Fiona Foley and the paintings of Paddy Bedford are examples of how completely different iconographies can reflect the same theme, influenced by the varied cultural understanding: political activism on the one hand and historical rendering or incorporation into the Ngarrangkarni on the other hand.

Appropriation Art

Consider Appropriation Art, an art genre whereby another artist's photographs, texts or works are included in one’s own. The technique was developed in Western Art at the end of the 1970s and achieved some prevalence during the 1980s. The purposes of Appropriation Art were manifold: the ironic modification of the original, the exposition of the problem of originality and creativity, a criticism of events in the art market, or even as a reference and homage to the original artist. Whether the original artwork is faithfully reproduced or modified is irrelevant to the genre.

Richard Bell (*1953) was politically influenced in his early adult life by the controversies surrounding the Tent Embassy (1972) as well as later by the 1988 Invasion Day (Bicentenary) events. He created his own form of Appropriation Art, which exhibited such a strong modification of the original artwork that he retained only allusions to a certain kind of painting, to a certain art genre. As an Indigenous artist he incorporated into his paintings the characteristic iconography of Western Desert art, including repetitive rasters in glowing colours or sometimes concentric circles, but he appropriated also the paint trails and paint splatter typical of Jackson Pollock. In this way, he opposed the oblivious absorption of Indigenous art by the white-dominated art market and reacted against the government policy of preferring to market all Indigenous art and culture as ethno-tourism rather than accepting and promoting Indigenous life and culture.

One of his most well-known paintings won the prestigious National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award in 2003. It is entitled “Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem)”. Immediately apparent is the text “Aboriginal Art it’s a White Thing”, which is deliberately confrontational to a white audience interested in Indigenous art. The text highlights the overpowering role of whites in the marketing and valuation of Aboriginal Art. When closely examined, further texts are decipherable in the black and white areas. Written in the white area is:

I am humiliated

I am sorry

Your ancestors were the kindest the most humane colonising power in the history of the world. They didn't steal our lands. You did in 1992. Your ancestors were very kind to Aboriginal people all over Australia. They gave work rations of flour, tea, sugar and even tabacco. And it is quite silly to think that work for ration was slavery minus the accommodation. You didn't commit genocide. You didn't even steal our children ...

I was wrong. You can justify everything.

Written in the black zone of the painting is:

I am not a racist

I just don’t like aboze, juze, wogz, slow pedz and reffoze

The confusion Richard Bell incites with these texts, where the standpoint of the writer is not immediately clear, is premeditated. It is crafted to provoke a complacent, white audience – which appreciates Indigenous art yet ignores or discriminates against Indigenous culture, sovereignty and history – out of its lethargy and into a considered judgment. He does not suggest the direction of thinking, only that people do so. Richard Bell succeeds in his goal of provoking viewers to reassess policies towards Indigenous people, and to reconsider their own privileged positions and comfortable assumptions.

Richard Bell created a scandal, not with this painting, but with the T-Shirt he wore when accepting the art award: the bold text on the chest proclaimed “White girls can't hump”. With this he held a mirror to white Australia by exchanging the racial roles. In ironical form, he reflected what Indigenous people hear daily:

… they fight too much, drink too much, fuck too much, waste their money and destroy property; they are unemployable, irresponsible, promitive, spiritual, close-to-nature, parasitic, disappearing, not black enough, violent, opportunistic. (Leonard, S. 24)

Richard Bell commentated on the indignation about “White girls can't hump” as follows:

"My art … is an in-joke for smart people, the smart people will get it and the rest of the morons won't." (Leonard, S. 5)

Richard Bell uses satire, humor and absurdity, to censure the huge discrepancy between the sham-egalitarianism of the art market, the allegedly “lucky country” myth of the white Australian world and the reality of discrimination and patronization experienced by Indigenous people.

Re-Appropriation

Gordon Bennett dares the further step, discussed below, of creating Appropriation Art from previously appropriated artworks. Examples of his work were exhibited in the 2012 dOCUMENTA 13 in Kassel, incited by works of Margaret Preston.

The Australian non-Indigenous artist Margaret Preston lived from 1875 to 1963 and is famous for promoting use of the symbolism and aesthetics of Indigenous art in developing a national Australian art movement. This was a complete annexation and re-definition of Indigenous iconography. Since Preston believed a national aesthetics could only develop on a foundation of broad acceptance, she proposed that Indigenous symbolism should be promoted in decorative design. Margaret Preston made corresponding design drawings in 1925.

Gordon Bennett (*1955) took those designs, then magnified them a hundred times in size and painted them in prominent acrylic colours on large canvases. The artist – who is an acknowledged master of Appropriation Art – thus achieves the unique strength of expression for which many artworks of the Western Desert Art are famous.

The essential point, however, is that Gordon Bennett redeems the designs which were exploited for decorative purposes, reuniting them with contemporary art. Moreover, he re-appropriates the Indigenous symbolism once appropriated by Margaret Preston, returning control and ownership to Indigenous hands.

Conclusion

The examples discussed show that Australian Indigenous artworks can be strongly political in character. The sampling was chosen to be in some way indicative. The impression that urban artists often use their art to protest past genocide or denounce ongoing discrimination is generally true, as is the impression that artists of the Western Desert area often restrict themselves to documenting past or present tragedies. The examples of Fiona Foley’s “Witnessing to Silence” and the work “Destruction I” concerning Maralinga by Kunmanara Queama and Hilda Moodoo, come immediately to mind. It is beyond all doubt that Kunmanara Queama made his artistic choices in the direction of chronicling, based on his cultural and artistic convictions, given that he dedicated much of his active life to political protest for land rights. Likewise, Fiona Foley’s dedication of her art to socio-political protest is reflected in her own writings.

However, it is not possible to generalize the iconography and visual semantics found across the full spectrum of such political artworks. Each artist, and even each artwork, adopts and adapts visual symbols and icons from the artist’s personal history and – through the genre of Appropriation Art – even from other artists, sometimes of opposite political conviction. The example of Gordon Bennett and Margaret Preston springs to mind. Furthermore, even a basic icon such as concentric circles representing an important place may have its imbued meaning metamorphosed from this is Pitjantjatjara country to this country has been obliterated to our culture has been absorbed.

While politics and icons are both hugely important in Indigenous art, it is the experience, insight and inspiration of the individual artist that determines how the two aspects are connected and what interpretations can be made.

Anmerkungen

(1) Allas, Tess: “History is a Weapon. Fiona Foley – History Teacher”, Artlink 30 (1) 56-61, 2010

(2) Araeen, Rasheed, Sean Cubitt and Ziauddin Sardar (Hg.): The Third Text Reader: On Art, Culture and Theory, Continuum, London 2002

(3) Cosic, Miriam: “Revealed: Message hidden in Sculpture”, The Australian, 10. März 2005 http://de.scribd.com/doc/6562841/FionaFoleyHidesMeaning

(4) Cumpston, Nici und Patton, Barry: Desert Country, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 2010

(5) dOCUMENTA (13), Das Begleitbuch/The Guidebook, Katalog/Catalog 3/3, Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2012

(6) Foley, Fiona: “The Elephant in the Room - Public Art in Brisbane”, Artlink 32 (2) 2012, S. 64-67

(7) Genocchio, Benjamin: Fiona Foley, Solitaire, Piper Press, Annandale 2001

(8) Kleinert, Sylvia and Neale, Margo (Eds.): The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, Melbourne 2000

(9) Leonard, Robert (Ed.): Richard Bell: Positivity, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane 2007

(10) Lüthi, Bernhard (Ed.): Aratjara. Kunst der ersten Australier, DuMont, Cologne 1993

(11) Maralinga Rehabilitation Technical Advisory Committee, Rehabilitation of former Nuclear Test Sites at Emu and Maralinga (Australia) 2003. Australian Department of Education, Science and Training, 2003. http://www.ret.gov.au/resources/Documents/radioactive_waste/martac_report.pdf.

(12) Mattingley, Christobel (Ed.): Survival in Our Own Land. ‘Aboriginal’ Experiences in ‘South Australia’ since 1836, Australian Scholarly Publisher, Adelaide 1988

(13) Museum of Contemporary Art (Ed.): Paddy Bedford, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney 2006

(14) Neale, Margo (Ed.): Urban Dingo - The Art and Life of Lin Onus 1948-1996, Crafts-man House, Brisbane 2000

(15) Public Art Agency, Arts Queensland, Department of Education and the Arts: 'Engagement: Art + Architecture. Art Built-in Brisbane Magistrates Court', Brisbane 2004, S. 17, http://www.artplace.arts.qld.gov.au/CMS/Uploads/Engagement%20art+architecture.pdf

(16) Sammlung Essl (Ed.): Dreamtime. Zeitgenössische Aboriginal Art, Edition Samm-lung Essl, Klosterneuburg 2001

(17) Warburg-Haus Hamburg, Forschungsstelle Politische Ikonographie, www.warburg-haus.de

(18) Warnke, Martin, Fleckner, Uwe and Ziegler, Hendrik (Ed.): Handbuch der Politischen Ikonographie C.H.Beck, Munich 2011

(19) http://jayyounger.com/?portfolio=fiona-foley-witnessing-to-silence (viewed15. September 2012)

(20) Bähr, Elisabeth: "Political Iconography in Indigenous Art", Zeitschrift für Australienstudien 27, 2013, S. 49-66, ISSN 1617-9900

![größeres Bild im neuen Fenster. Fig. 6: Fig. 6: Fiona Foley, Witnessing to Silence, 2004, bronze, water feature, pavement stone, laminated ash and stainless steel; printed in: Foley, Fiona, 2012. “The Elephant in the Room – Public Art in Brisbane”. Artlink, 32 (2) 67 and [19] größeres Bild im neuen Fenster. Fig. 6: Fig. 6: Fiona Foley, Witnessing to Silence, 2004, bronze, water feature, pavement stone, laminated ash and stainless steel; printed in: Foley, Fiona, 2012. “The Elephant in the Room – Public Art in Brisbane”. Artlink, 32 (2) 67 and [19]](../images/Fiona_Foley_Witnessing%20to%20Silence_z1.jpg)